The seventh episode of Cosmos, “The Backbone of Night,” is about scientific curiosity and the history of that curiosity—its evolution, and its suppression. The episode begins in Sagan’s present-day Brooklyn with him guest teaching in a classroom where he attended school as a child, then jumps back to ancient Greece. Finally, it trends forward to his contemporary setting again, with a few familiar stops on the way. As Sagan’s memorable introduction says, “The sky calls to us. If we do not destroy ourselves, we will one day venture to the stars. […] In our personal lives, also, we journey from ignorance to knowledge. Our individual growth reflects the advancement of the species.” This is an episode about those things: knowledge, advancement, individual growth, and the questions that drive them all.

Similar to the previous episode’s focus on exploration, this is a big-idea-narrative, too. It’s also connected to exploration, but is more about the force driving that push to the stars: passionate questioning. In terms of that questioning, the audience gets both a Western history of it—via the Greeks—and a Western history of suppression and mysticism, from Pythagoras through Christianity. It’s one of the sharper-edged episodes, at moments. However, it also functions as a sort of summation of the episodes that have come before it.

Every one of us begins life with an open mind, a driving curiosity, a sense of wonder.

This is an episode that I remember well from my youth, and it’s also the source of some of the more oft-quoted lines from Cosmos as a whole. That’s probably because the focus on curiosity and the questioning mind, from children to ancient Greek scientists, is at once personal and grandly universal. The dialogue it provokes is one of great change and great understanding, with sweeping invitations to thought, and through thought, the stars. As with the previous episode, here Sagan seems to be arguing for an essential part of human nature—whatever we may now make of any essentialist claims—and, in this case, it’s a driving curiosity, and that sense of wonder that science fiction fans are so familiar with.

The balance between this dialogue of great openness and innovation and the episode’s co-narrative of the ways that mysticism—particularly religious mysticism—stifles openness is remarkably delicate. Too far to one side and it’s a utopian story about how awesome thinking is; too far to the other and it becomes too militantly atheist for a mainstream audience to remain engaged. Sagan’s genuine engagement and enthusiasm, as well as his poetic diction, are part of what keeps this sensitive balance functioning, and so is the episode’s general focus on children, a child’s mind, and the sense of wonder a child gains from asking questions and finding answers. The serious middle of the episode, where the criticism happens, is bracketed by classroom teaching scenes that are down-to-earth and touching. I don’t think that’s any accident, personally.

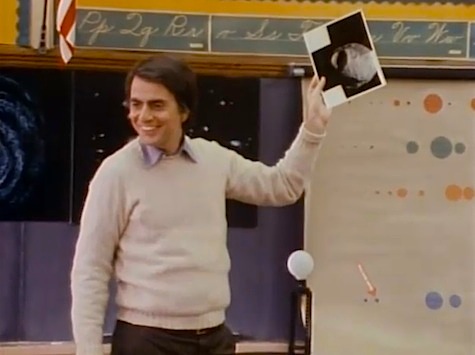

The opener really softens up the audience—Sagan’s childhood reminiscences of Brooklyn, as his adult self wanders the city, are delivered with a kind of intimate grace that invites the viewer at home into Sagan’s own heart and mind. The story about going to the library for a book on stars, and how his mind opened up upon reading about space, is a familiar one for many people, and an excellent place to start an episode about curiosity and the power of questioning. At some point, most of us have experienced the moment when “the universe had become much grander than I had ever guessed.” That we then move into a classroom of interested and active kids, learning about the cosmos from Sagan himself, continues the positive feelings evoked by the opener. I mean, who can resist hearing him say things like, “there’s a large potato orbiting the planet Mars?”

I still laugh at that line. It’s clever and cute, and just right for the small-person audience he’s got on the edge of their seats.

But, what is all this about questioning? The meat of the episode isn’t the cute parts at the beginning and end about kids and Sagan’s childhood. It’s about the first Greek scientists, who thought and questioned and explored—who were passionately curious. We’ve talked about them before; when I say this episode is a bit of a recap, that’s because in the trip through time we visit many of the places we’ve been before. Sagan touches on Aristarchus, Kepler and the Dutch again; the same footage from those respective episodes appears once more. However, this time, they’re being interpreted in a larger framework. He taught us about the facts first—and now he’s exploring what we can deduce from them. Scientific thinking in action.

He also returns to ideas about mysticism from the episode that skillfully takes down astrology—a thing most folks aren’t too defensive of—and stretches them to the next logical conclusion: the conflict between “cosmos and chaos,” “nature and the gods.” It’s about much more than just how silly astrology is this time. Rather, it’s about how dangerous mysticism has actively suppressed, stifled, and destroyed scientific interest and knowledge. This argument is framed subtly in terms of Christianity and contemporary religion, though Sagan takes plenty of hard shots at Pythagoras and Plato (who quite deserve it).

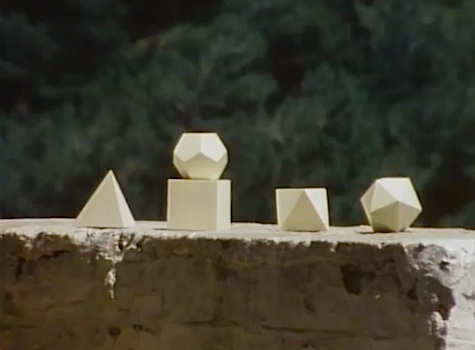

As for them, he lays out the Pythagorean hypocrisies and the Platonic ethical fractures in a short and powerful argument that I still find useful to this day. “Ordinary people were to be kept ignorant,” Sagan says of the Pythagoreans’ work. “Instead of wanting everyone to share and know of their discoveries, they suppressed the square root of two and the dodecahedron.” And Plato loved the elitism and secrecy, equally, as he argues. Plato was hostile to the real world, experiments, practicality, etc.; his followers eventually extinguished the light of science in Ionia. And it stayed that way until the Renaissance. That’s a sobering fact, and one that would make most audiences—now comfortable, after six episodes and the gentle opener to this one, with having their minds opened a bit—feel at least a touch of discomfort.

So, why the mystics over the scientists? I still think Sagan’s argument holds true today, when he says that “they provided, I believe, an intellectually respectable justification for a corrupt social order.” Issues of slavery had to be glossed over in this philosophy, for example; the physical world had to be divorced from thought. They alienated body from mind, thought from matter, and divorced earth from the heavens—divisions which were to dominate western thinking for more than twenty centuries. The Pythagoreans had won. Sagan says it much like that, and I can’t sum it up any better—the mystics had won; they supported elitism and limited power. Experimental science, on the other hand, asks us all to question, to be curious, to insist on finding answers.

People who insist on finding answers aren’t very good for a corrupt political and social order, or for mysticism.

The argument for science and curiosity over mysticism in this episode is the strongest yet, and it’s a theme that Sagan returns to over and over, ever closer and ever sharper, easing the audience into it. Then, having done the hard work, we return to the classroom and the sense of wonder for one of my favorite Sagan monologues ever:

As long as there have been humans, we have searched for our place in the cosmos […] we find that we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe in which there are far more galaxies than people. We make our world significant by the courage of our questions and by the depth of our answers.

Yeah. That sounds just about right to me. We are cosmically insignificant, and yet ultimately significant in a grander way because our participation in the knowing and understanding of things, our curiosity, our drive. Sagan’s pretty much the best we’ve had in the West at distilling scientific wisdom into poetic, lovely, important truths that we can use to better structure our understanding of our universe, and also our empathy.

*

Come back next week for episode 8, “Travels in Space and Time.”

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.